Work-arounds to racism—a speaker’s comments or actions that avoid explicitly naming the identity of the person targeted, for instance—do a complicated harm. Work-arounds allow habits of thinking to stand: if you don’t explicitly say something, if you don’t analyze yourself to determine the why behind your treating of two people in different ways, you can let yourself off the hook easily, even as the other person is left holding your feelings. It is uncomfortable and inconvenient to dig deeper into one’s own psychological recesses to find a why—as we might see from the American worship of big-box stores, comfort and convenience are staples of our culture. One of the great powers of the social novel as a form is to reveal the interiority of characters and, from that inner stew of experience, dramatize or call attention to the story’s surface the patterns of behavior that arise between people and cause problems.

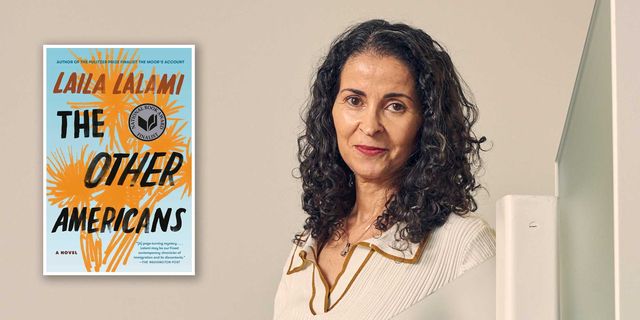

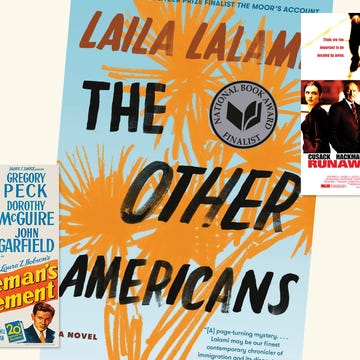

Laila Lalami’s The Other Americans, the March California Book Club selection, is a particularly memorable social novel. It opens with Nora Guerraoui, a daughter learning of the death of her Moroccan immigrant father, Driss, in a hit-and-run in the Mojave Desert. There are, in this concept for the book, shades of Albert Camus’s The Stranger and the Cure’s “Killing an Arab,” the latter of which caused an uproar and was misappropriated for harmful ends, but Lalami’s book takes a different tack: her artistic choices are carefully realistic and nuanced in the particulars, if politically unambiguous as a whole. When the police come to investigate, they ask questions about whether Driss had financial woes, drug or gambling problems, enemies. Nora notes the difference between their questions—work-arounds—and her own: “Who was driving the car and how did they hit him and why did they flee the scene?” The former set of questions is based on stereotypes of brown men, a way to psychologically restack the cards against them, to implicate them in their own undoing, while the latter questions are what you’d ask if you understood, implicitly, that the person hit by the car was a victim. As Nora remarks later in the book, “I had long ago learned that the savagery of a man named Mohammed was rarely questioned, but his humanity always had to be proven.”

Nora explains her dreaminess as a survival mechanism at a school where, as for many immigrants, the teacher could not pronounce her name and, rather than make the minor effort to say it, instead pointed her background out to the class, publicly framing her as other. It’s an attitude toward society that permits other students to also target her. In Nora’s case, the children show their own contempt by comparing the eggplant she brings for lunch to poop. Wanting to improve the odds of justice and balance the scales, when Maryam, Nora’s mother, speaks to the detective investigating Driss’s death, she tells all the details of moving to the United States, and underneath that, it seems, is a desire to make sure the detective understands that she and Driss are humans with an origin story.

Of course, there is also direct, clear-cut violence, and we can see the horror of that more readily—Nora remembers that after 9/11, her father’s business was set on fire and the crime went unsolved. “And then he put up a huge flag outside his restaurant, like he had to prove he was one of the good ones.” The Other Americans remains an acutely important read five years after its publication. We live in a time when the media lays greater emphasis on whether or not comedian Hasan Minhaj was entitled to use fiction about the real-life hate and surveillance that Muslim Americans endured after 9/11 in his stand-up than on how terrified Muslims have been made to feel by the behaviors of the government and dominant groups for decades. In fact, the anxieties around Islam and brown people more broadly were so tremendous after 9/11 that a purportedly freedom-loving people became willing to be watched indefinitely by their government.

Even in California, arguably the most multicultural state, suspicion and violence were thrown at anyone who fit some vague idea of what a Muslim might look like. The jump in hate crimes in 2001 after 9/11 was nationwide; in Los Angeles County alone, the numbers jumped from 12 hate crimes against those of Middle Eastern descent in 2000, compared with 188 similar hate crimes in 2001. In all likelihood, as various organizations have recognized, hate crimes are underreported because immigrants of color often fear getting the government involved in their lives at all. Fear of being mistaken for an enemy by men with guns persists for brown people to the present. Lalami touches on the expansive nature of this alarm as she elaborates on the friendship between Nora and a classmate, Sonya Mukherjee. Both were thought to be Muslim, with Sonya explaining to others that she wasn’t, but, as Nora notes, after 9/11, “that distinction seemed to matter less, not more. We were both called the same names. Ragheads, Talibans. Sometimes raghead talibans.”

Nine voices relate the aftermath of Driss’s death, including the largely lackluster police investigation into the hit-and-run. In the course of this investigation, Nora runs into Jeremy, an Iraq War veteran with whom she used to go to school. Initially, it’s in their relationship that a reader can most see the subtle—and suspenseful—complications of mainstream America’s contemporary outlook on racism and xenophobia.

Jeremy is a sheriff’s deputy—a man with a gun—and a kind of worry, engendered by the opposition between his position and Nora’s, hangs over the story. But he was one of the good kids in the middle school band Nora played in; she notes that his “first instinct wasn’t to ask, ‘What are you?’ but ‘What do you play?’” His subsequent history is murkier. His buddy, for instance, wears the shirt of a sniper—One Shot, One Kill—and he doesn’t blink. He used racist slurs to help himself dehumanize the enemy while fighting in the Iraq War. He is angry that people see him as a “political prop” or “movie fantasy” because of his uniform, and he is angry about accompanying his friend to an anger-management group. When he reveals that he’s a vet at their first dinner together, Nora is reminded of the Marine flags in their hometown and thinks, “So it shouldn’t have surprised me so much that Jeremy had enlisted, and yet it did. I couldn’t reconcile the memories I had of the stuttering boy in grade school with the reality that he was an agent of the state.” Balancing this, we see through Jeremy’s eyes that he’s felt a sense of unbelonging, too, for different reasons.

When Nora reveals that the son of the man who confessed to killing her father had written “raghead” on her locker, we realize that perhaps a work-around has occurred, perhaps the hit-and-run was not, at least not entirely, an accident but motivated by wrath. Yet Lalami maintains a strong sense of classical balance, an Apollonian aesthetic, in her fiction. For some of the residents of Yucca Valley and Joshua Tree, the life of an immigrant is disposable, and yet, as they speak, revealing their own lives and feelings, we might find ourselves sympathizing with their grief that their home has been transformed into a place where they, too, no longer belong.

There’s a moral heft in these pages, a kind of cleansing compassion, that harks back to novels from the 18th and 19th centuries. A lesser or untrusting artist might try to slip in preachy exposition, but Lalami has an eagle eye for lived reality, a reality that remains underexpressed still, five years after the publication of The Other Americans, and the care with which she dramatizes age-old questions of unbelonging, as they unspool in post-9/11 Joshua Tree, through the novel’s tiniest details is masterful.•

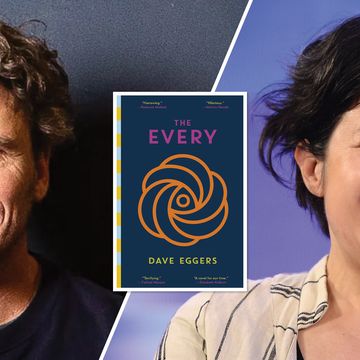

We will be meeting this Thursday, February 29, at 5 p.m. Pacific time to gather together author Dave Eggers, host John Freeman, and special guest Caterina Fake in a discussion of The Every. Our apologies again for needing to cancel last month, but we know you’ll enjoy this conversation just as much on Thursday. And please mark your calendars and join us on March 21 at 5 p.m. Pacific time, when Lalami will appear in conversation with Alta Journal books editor and guest California Book Club host David L. Ulin and special guest Danzy Senna to discuss The Other Americans. Register for the Zoom conversation here.

WEIGHT OF SILENCE

Writer and former assistant editor of the CBC Rasheeda Saka analyzes The Other Americans, writing that it is “filled with such a multiplicity of voices that those voices, paradoxically, carry the weight of heavy silences.” —Alta

ACROSS GENERATIONS

Fiction writer and critic Ilana Masad reviews Amanda Churchill’s debut novel, The Turtle House, set in Texas, in which a young woman develops a strong relationship with her 73-year-old grandmother, even though the only thing they “have in common is that they’re in limbo.” —Alta

OLD FRIENDS

Jack Boulware, the cofounder of Litquake, writes about wandering San Francisco with comedian and podcaster Marc Maron and taking a look at their past haunts. —Alta

INDIE SALES

Here are the books that were bestsellers at California independent bookstores for the week ending February 18, 2024. —Alta

“MOON OF PURE FIRE”

Read Dean Rader’s poem “California Villanelle.” —Alta

FANTASTICAL BORDERLANDS

Stephanie Elizondo Griest reviews author and Alta Journal contributor Lauren Markham’s A Map of Future Ruins: On Borders and Belonging, calling it “the most expansive contribution to border literature I have yet to read.” —Los Angeles Review of Books

Alta’s California Book Club email newsletter is published weekly. Sign up for free and you also will receive four custom-designed bookplates.

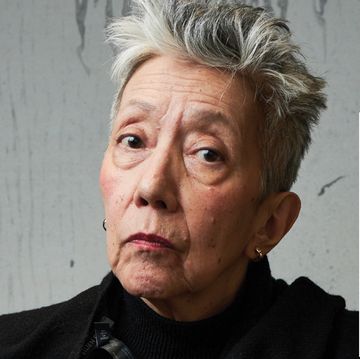

Anita Felicelli, Alta Journal’s California Book Club editor, is the author of the novel Chimerica and Love Songs for a Lost Continent, a short story collection.