In one of the photographs, the sign is no taller than the sagebrush. It stands in the foreground, nailed to a weathered post, and reads, “Hidden Rancho.” In the distance, past a trio of Joshua trees, the house sits at the end of a white-sand road. My stepmother’s white Valiant is parked nearby. The house is small, flat-roofed, a hyphen in the expanse of the desert, set back from Highway 62 in a wash that runs along the Morongo Basin just west of Yucca Valley. The house is my father’s, where he lived during the years I rarely saw him—a place that was refuge from a string of disappointments, bad luck, and tragedy.

Like author Laila Lalami’s character Nora Guerraoui in The Other Americans, my father “never belonged to any tribe.” The son of immigrants, he was restless, seldom at home anywhere. His father, a baker and confectioner, was from Damascus, his mother Istanbul, and in the many houses where my father lived, there was an element of escape—from the past, from a history he didn’t want, and from the losses that led him to Yucca Valley, where for a time he was happy.

And like Nora’s father in The Other Americans, Driss Guerraoui, a student of Sartre and Lévinas turned business owner, my father was derailed from his youthful path. At 18, he was accepted to the Yale School of Architecture, but my grandfather, not knowing of Yale’s prestige, refused to pay the tuition. My father never returned to school, taking art classes at night instead. Like Driss, he worked many jobs to survive: freelance graphic design, coin-op laundry franchises, and later a mail-order business. When my sister and I were small, he worked from home, co-parenting us at a time when fathers rarely did. We lived in the foothills of Los Angeles then, in a canyon house my father loved. Alpine, rustic, spacious, with open-beam ceilings, the house’s rooms were paneled with silvered redwood, sandblasted until the grain ran like windblown sand. Then came the divorce, and visits from my sister and me were limited to weekends and two weeks in summer. In those years, the house was a respite, but in 1967, it was destroyed in a canyon fire fueled by the Santa Anas that come in October and send gusts ripping toward the mountains. After the fire, my father turned rootless, distant, and the once-regular visits with him became sporadic.

Bad luck and missed opportunities seemed to trail my father, and people inevitably disappointed him, so he came to rely on landscapes. He spoke often of the thin, clean air of the Sierra. The pretty western towns along the 395. The wildflowers on the desert floor of Borrego Springs and the red hills and scrub of the Morongo Basin. After the fire, he split his time between Yucca Valley and the apartment my stepmother, Hortensia Sandoval, kept in L.A. to be nearer to her teaching posts.

Was my father happy in Yucca Valley? In the ’60s and ’70s, the town was the province of white Americans, transplants from L.A. and the Midwest, the descendants of homesteaders. Some, it is documented, came by covered wagon from Fullerton. The farms were eventually parceled off into country clubs and strip malls like the one in Banning, where my father owned a coin laundry. He shared the local ethos of self-reliance and conservative politics, but as an Arab man, my father would have “stood out like a tall weed in a clipped hedge,” as Lalami describes Driss, and so he kept to himself on the property at the city’s west end off Pinon Drive, averse to the local pancake breakfasts and Fourth of July parades.

I visited the house in Yucca Valley only twice, in summer, when the heat bakes the ground and silences the landscape. It’s the silence I remember, and the cloying heat of the house’s small rooms. Like in Driss’s cabin, there was an atmosphere of temporariness: “a small kitchen, with two stools at the counter, and a Formica-topped table with an unsteady leg.” I recall my sister and me eating cereal from small boxes. The buzz of my father’s table saw in the desert. At 14, restless in the desert’s stillness, an afternoon I spent in the garage at a workbench, drawing in a sketchbook. Out the small window, the valley ran in a field of red earth dotted with Joshua trees I would one day write into a story as “shaggy silhouettes like unkempt boys loitering outside our door.”

I wish I’d spent more time there—wish I’d known a desert spring, or winter, when the air is sharp and clear—but after a decade, my father sold the house. There seemed to be money troubles, uncertainty about where he and Hortensia would live when he loved the wilderness and she the city. One winter, Hortensia snapped a photo of my father standing outside the house. In a rare snowfall, he’s sweeping snow off his car. Like the dim memories Nora’s Morocco-born sister, Salma, has of Casablanca, I hold memories of Yucca Valley, indelible images of the desert, and of my father, who in those years was a mystery. “How is it possible to miss someone you don’t remember?” Salma wonders. “And yet,” she says, “you do.”•

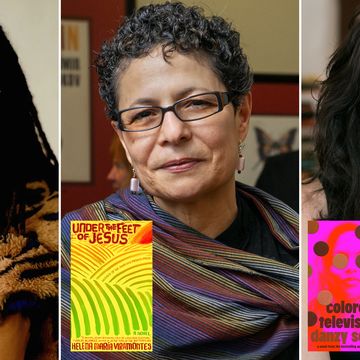

Join us on March 21 at 5 p.m. Pacific, when Lalami will appear in conversation with Alta Journal books editor and California Book Club guest host David L. Ulin and special guest Danzy Senna to discuss The Other Americans. Register for the Zoom conversation here.

Lauren Alwan is a writer whose fiction and essays have appeared in ZYZZYVA, the Alaska Quarterly Review, Catapult, and others.