Words are funny things. They are symbols, which means that, in the right writer’s fingertips, they become passageways to other times and worlds and lives. But words are also sounds: our tongues roll out l’s and hiss sibilants, and when our mouths dance them into life, our words, just for a moment, become solid. We feel them as surely as we feel the earth pushing up against our feet. The best writers somehow manage both: words that soar and yet also have the immediate, physical solidity “of bark, leaf, or wall / riprap of things,” as Gary Snyder, among the nimblest of American writers, puts it in his poem “Riprap.”

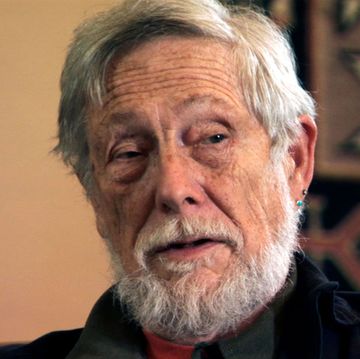

Words also have histories. They have their deep etymologies, of course, but the words a writer chooses, I have come to believe, are also marked by that writer’s life. Surely it is of interpretive importance that Snyder was born during the Great Depression and spent his early years on a two-acre farm near Puget Sound, big enough for only three Guernsey cows, on a patch of land that had just been cleared of its ancestral forests and that today is part of the greater Seattle sprawl. “I remember my father dynamiting stumps,” he writes of his parents’ farm in The Practice of the Wild. “Two or three of the old trees had survived…and I climbed those, especially one Western Red Cedar (xelpai'its in Snohomish) that I fancied became my advisor.”

Snyder has lived a long and wild life—he has traveled the world; studied Zen on two continents; penned a few hundred poems and translated scores more from Chinese into English; worked as a logger, a fire spotter, and an English professor; witnessed the birth of Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl”; played one of the leading men in Jack Kerouac’s The Dharma Bums—and everything he found is all there, in The Practice of the Wild, a book of essays and philosophy published in 1990, when Snyder was 60. It’s the sort of book that, if written by anyone else, would have been the culminating gift of a long career—but Snyder, now in his mid-90s, is still writing. But neither is The Practice of the Wild a career midpoint. Instead, it’s the locus around which more than 65 years of writing turns, and it, too, has a center: that old tree to which he apprenticed. The whole book—Snyder’s whole writing life—is the tale of what the cedar taught him.

There’s no one way into The Practice of the Wild. It’s not so much a thesis-driven book as it is a circumambulation around both the idea and the physical reality of the wild. Many of us might be used to thinking of the wild and its close cognate, wilderness, as an idea and a place that is fundamentally nonhuman—or, to put it in the words of the 1964 Wilderness Act, a place “hereby recognized as an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” But Snyder is quick to point out in the preface that the wild is nothing more than “the richness of plant and animal life on the globe including us, the rainstorms, windstorms, and calm spring mornings…the real world, to which we belong.” The wild is the very condition of life itself—we are wild, we are part of the community of life, we always have been, and, to the extent that humans will remain creatures on earth, we always will be.

We might be used to thinking of wild things and places as dangerous, disordered, and threatening—nature red in tooth and claw, lives that are nasty, brutish, and short, that civilization brings control and stability. But Snyder is a student not only of Zen but also of anarchism (he once wrote, in an essay originally titled “Buddhist Anarchism,” “The national polities of the modern world maintain their existence by deliberately fostered craving and fear: monstrous protection rackets”). Both Zen and anarchism hold that suffering is caused by the human desire for control, that grasping after it lays waste to our inner lives, our social lives, and all earthly life. “It is not nature-as-chaos which threatens us,” Snyder writes in a chapter from The Practice of the Wild called “Good, Wild, Sacred,” “but the State’s presumption that it has created order.” Peaceful coexistence lies in something much deeper, much older: “The world is nature, and in the long run inevitably wild, because the wild, as the process and essence of nature, is also an ordering of impermanence.” And both Buddhism and anarchism hold that a good life, a good world, is to be had not simply by thinking the right thoughts but through practice, that, reciprocally, if the wild is the condition of life, then the practice of a good life must nurture the wild, impermanent condition of all things.

The Practice of the Wild is richly spiced with anecdotes, both historical and personal, on wild living, but the practice Snyder returns to throughout the book, and develops in two standout linked essays, “The Etiquette of Freedom” and “Tawny Grammar,” is the wrangling of words. Cedar trees and rainstorms and calm spring mornings may be material manifestations of the wild, but it is with language that we humans fashion our sense of the world. It is with language that we try to understand our condition, our human condition of wildness, and it is with language that we are, in part, continually reborn in wildness and gift that wildness to others. In our own time, there is a curious effort to claim that language is inherently deadening—think of Robin Wall Kimmerer’s insistence that English grammar can lead to exploitation, or Paul Kingsnorth’s argument that every language severs our connection with the wild—but Snyder, who is a historian of language, knows that “languages meander like great rivers leaving oxbow traces over forgotten beds.… Language is like some kind of infinitely interfertile family of species spreading or mysteriously declining over time, shamelessly and endlessly hybridizing, changing its own rules as it goes.” Language, like humanity itself, is a wild thing, and one way to cultivate the wildness of the earth, the wildness in ourselves, is to pay close attention to the words we use, our grammar, our syntax. Think of how Snyder’s similes give his sentences life—language that meanders like a river, both purposive and unpredictable as it courses to its ultimate destination. Think of the tree on his parents’ farm, think of how it changes, think of the different histories evoked, if one calls it western red cedar; or by one of its Native names, xelpai'its; or again, scientifically, Thuja plicata; or teacher. Notice how each word feels different on your tongue as you speak it.

And here we are, back at the beginning, contemplating Snyder’s words. “Lay down these words / Before your mind like rocks,” the poem “Riprap” begins. I will admit that I am always brought up a little short by his writing, whether prose, poetry, or some wild hybrid of the two, for I tend to associate, as well as to practice, a kind of literary wildness with circuitous, branching, unpredictable sentences that pick their way like game trails through the woods. By contrast, there’s a plainspoken simplicity to Snyder’s writing, which is not to say that it is simplistic or simpleminded, just as there’s nothing simplistic or simpleminded about a centuries-old cedar. There’s a miraculous givenness to all of Snyder’s work, a solidity that gives me pause, that makes me pause, his words like rocks that have endured for ages yet miraculously continue to shine for those who take their time.•

Join us on May 16 at 5 p.m. Pacific time, when an array of panelists and CBC host John Freeman will gather to celebrate and discuss Riprap and Cold Mountain Poems and The Practice of the Wild, with an appearance by author Gary Snyder. Register for the Zoom conversation here.

Daegan Miller is an essayist, a critic, and a historian. He is the author of This Radical Land: A Natural History of American Dissent.