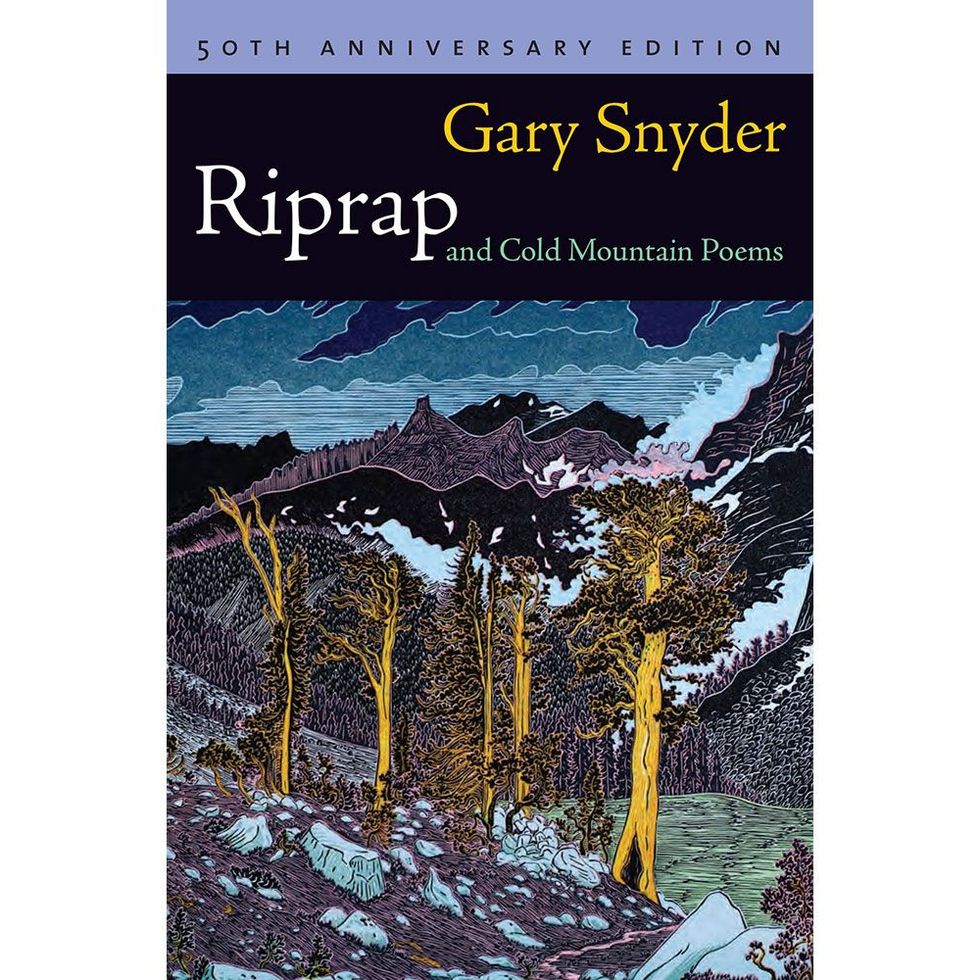

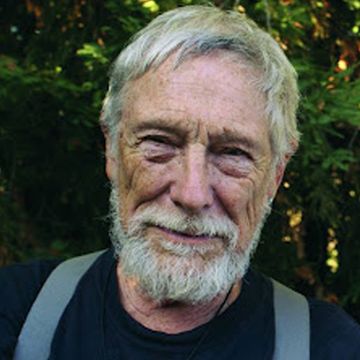

My favorite of Gary Snyder’s many books is his debut: Riprap, available for many decades in a volume with his translations of the seventh-century Chinese poet Han-shan’s Cold Mountain Poems. There’s something perfect—or perfectly Snyderesque—about the interplay: his work, spare, rough-hewn, juxtaposed against that of the ancient poet of whom he writes, “He looked like a tramp. His body and face were old and beat. Yet in every word he breathed was a meaning in line with the subtle principles of things.”

That’s a simple description, three declarative sentences. But the weight of them together tells us something not only about Han-shan but also about Snyder himself. Let’s start with the use of that word “beat,” which had already become a cultural signifier by the time the poet thought to use it, popularized (in the United States, at any rate) by Jack Kerouac, his compatriot. Kerouac’s novel The Dharma Bums—which revolves around a Snyder alter ego named Japhy Ryder—was published in 1958, a year before Riprap appeared.

This article appears in Issue 27 of Alta Journal.

SUBSCRIBE

Snyder was no Beat, not really, although he shared similar concerns. These include “the subtle principles of things,” which Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg also sought to investigate: the idea that writing, or poetry, might offer access to a sharper apprehension of reality, if we can only still ourselves.

“Down valley a smoke haze / Three days heat after five days rain,” Snyder writes in “Mid-August at Sourdough Mountain Lookout,” which begins Riprap. The image is as unadorned as a pencil sketch, yet it leads to a subtle opening: “I cannot remember things I once read / A few friends, but they are in cities.” Here we see the grace of his vision, an appreciation on the one hand of nature and on the other of human evanescence. Even when young (Snyder wrote the poem in his early 20s), we must exist in the presence of loss.

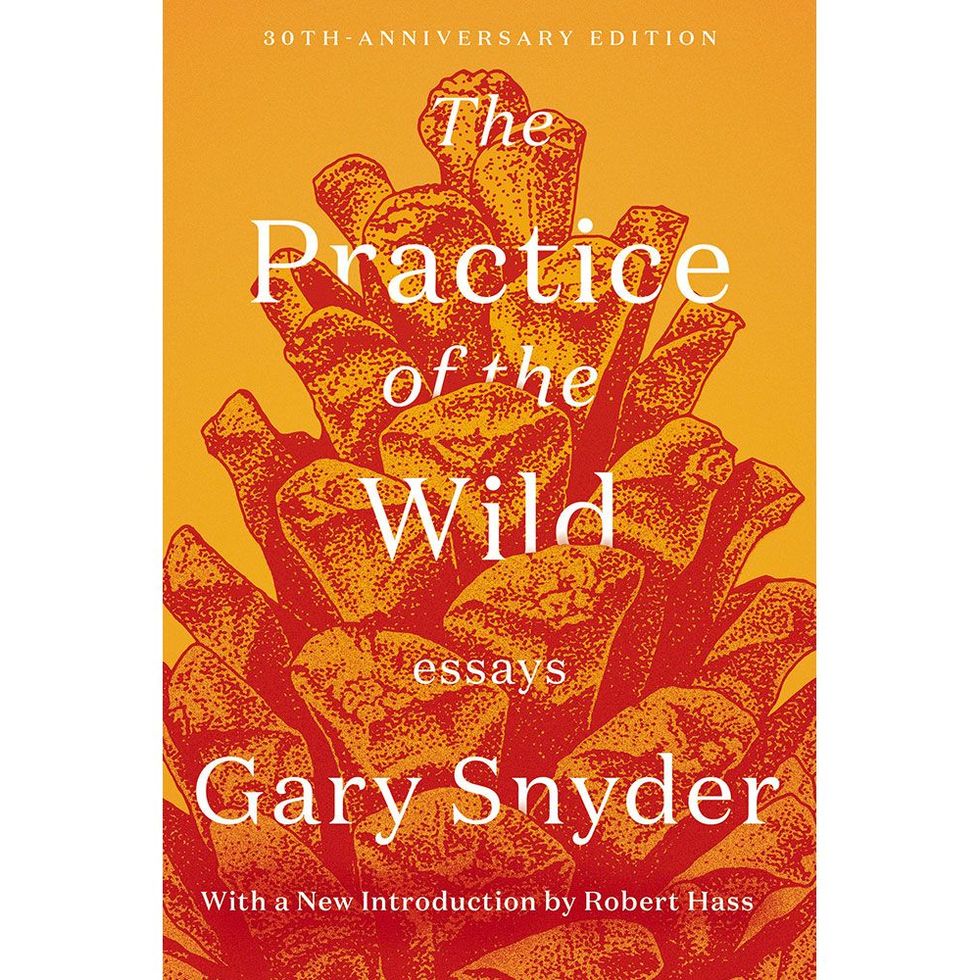

Everything is there: the tight lines, the acceptance, the wisdom, the understanding that we exist at the world’s mercy rather than the other way around. The subject also infuses Snyder’s nature writing, including 1990’s The Practice of the Wild, where he looks at wildness and spirit, at wilderness and what it means.

In Riprap, we see the origin story of Snyder the ecologist. His poetry and his activism have long been intertwined. Even the collection’s title reflects this: riprap, “a cobble of stone laid on steep, / slick rock to make a trail for horses / in the mountains.”

It’s in that definition, a stunning integration—the horse trail built by humans using stone and gravity, a construction that works within the landscape, augmenting as an act of care. Snyder’s writing functions similarly, offering a knowledge that feels if not ancient then certainly hard-won. “Thinking about a poem I’ll never write,” he admits in “A Stone Garden.” Still, in mentioning it, he brings the poem to life. The same might be said of every dream, which means, whatever else it is, Snyder’s work is a gesture of generosity.•