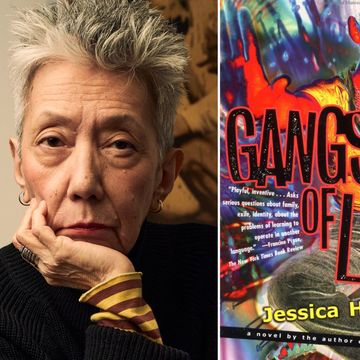

The small-press scene in the San Francisco Bay Area—and on the West Coast, more broadly—has been vibrant and busy for more than half a century. Describing San Francisco in the 1970s, author Jessica Hagedorn wrote that it “seems to be more a city of musicians and poets than anything else.” Many notable authors of the West, especially those with experimental or avant-garde books, got their start publishing with small presses, including Gary Snyder, Frances Mayes, and Charles Bukowski. Similarly, many midlist authors have left large publishers and escaped to small presses. A few weeks ago, however, the intrepid publishers around the country that make up the overall community received a shock. Small Press Distribution, colloquially known as SPD, which was founded in 1969 by Bay Area booksellers Peter Howard and Jack Shoemaker to distribute small-press titles that large distributors wouldn’t take a chance on, abruptly shuttered.

SPD had long maintained a warehouse in Berkeley. Back in March 2023, the distributor announced it would close its West Berkeley warehouse and initiated a GoFundMe campaign to transfer more than 300,000 books to the warehouses of Ingram Content Group in Tennessee and Publishers Storage and Shipping in Michigan. However, in the past few weeks, independent presses served by SPD were told that within the next 60 days they would need to claim transferred inventory and tell Ingram where to send the stock at their own expense. PSSC emailed the publishers to tell them their options. The presses have been searching frantically for solutions.

An unusual possibility has emerged for those of a particularly entrepreneurial spirit. Asterism Books, a trade distributor and online bookstore, was cofounded in February 2023 by Joshua Rothes, a visionary Seattle-based author who is also the publisher of Sublunary Editions, which he began in 2019 with the mission of publishing brief forms of literature, many of them works in translation. Two standouts, from my perspective, are What the Mugwig Had to Say, a long story by Julio Cortázar and artist Julio Silva, translated for the first time into English by Chris Clarke, and the novella Mystery Train, by internationally acclaimed author Can Xue, translated by Natascha Bruce.

During the pandemic, an online community of literature lovers built around Sublunary, which currently publishes 10 to 12 books a year and puts out the literary journal Firmament and the Empyrean archival series. Rothes also became a copublisher of Hanuman Editions. Late last year, one of Sublunary’s books, Lee Seong-Bok’s Indeterminate Inflorescence, translated from the Korean by Anton Hur, went viral after being long-listed for the National Book Critics Circle’s Gregg Barrios Book in Translation Prize. Rothes hadn’t yet put the book on Amazon and directly sold more than 1,000 copies to readers in two days. Once news of SPD’s closure hit, Asterism was unexpectedly shifted into the spotlight as a potential, novel solution for small presses and micropresses. Unlike SPD, Asterism doesn’t allow returns on wholesale orders of books, with exceptions for event orders and damaged copies, and in exchange for bookstores accepting this model, Asterism promises not to sell the books to Amazon or other marketplaces that impose discounts to undercut bookstores on price.

Last week, Rothes began working full-time on Asterism and his other ventures in support of other authors. Asked about his path to this moment, he jokes over Zoom, “I just wanted to write.” This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

The West Coast has always been a place of innovation for small presses and micropresses. Our separate sphere of small publishers is such a different world than that of the hierarchical New York houses. Are you getting a flood of inquiries?

We have received well over 80, possibly more, since last time I counted the rows in the Excel sheet, either through our website or by presses reaching out and saying hi. We’ve also done our best to be proactive in reaching out to presses we know; we’ve had conversations where we’ve said, Oh, we’ll talk one of these days. I don’t think anyone expected that day to come quite so abruptly.

You heard about it when the rest of the public heard about it?

One of my authors from Sublunary texted me and said something like, It’s a good thing you left SPD when you did. And I said, That’s an odd thing to say, since I haven’t been there in a few years. And then, ding ding ding ding ding ding ding ding. I was fully prepared to be doing other things that day.

What problems did you see that led you to want to create your own distribution model?

We’ve always done small print runs, usually through Bookmobile in Minneapolis. When I signed up with [SPD], I thought, I’m not quite sure how this is going to work, but it seems like everyone else is doing this—a lot of the presses I admire. I was happy in 2020 when I got accepted.

And then, one starts to see the checks come in and gets a sense of, How exactly is this helping cash flow for small presses? There are different aims, obviously, from a small press’s standpoint. Nonprofit presses generally have to show that they’re doing the work to get the books out there. They’re trying to justify [themselves by showing], Here’s how we’re helping get books out there. And distribution is a piece of that. Why people would go with Lightning Source or Ingram Spark is to get the books in all those places; you can upload a PDF and magically it’s available through Ingram, Amazon, target.com, barnesandnoble.com. But that ultimately doesn’t mean that there is someone advocating for the books. I wasn’t sure what those efforts were.

I didn’t have real transparency with SPD, unless I went and asked for sales reports. A lot of those books were sold forward into Amazon or Ingram or Baker and Taylor, and then you really don’t have data on where those go elsewhere. The model was untenable. They take 50 percent of net and fees. The numbers didn’t pencil out, and of course, there were the very public allegations of worker mistreatment and wage theft that came out.

Those two things combined made me think, I can leave this and try something. Initially, it wasn’t, I’m going to leave this and start a distributor. It was, I’m going to leave this and go back to taking bookseller orders, special orders, on my website. It was only after some conversations with other presses that Asterism started to take shape in its nascent form.

Who were your cofounders or partners in putting Asterism together?

Version one of Asterism was meant to be this utopian, decentralized co-op of small presses where a few of us got together—some that were with SPD and left around the same time I did, like Sagging Meniscus and Kernpunkt, and then some were presses that, maybe having more foresight than I had, didn’t sign up with SPD, like 11:11 or Contra Mundum or Inside the Castle. Asterism version one was a website that only dealt with wholesale orders and offered a one-stop shop for booksellers to order from all of our presses. We were each responsible for our own fulfillments and invoicing, and the entity didn’t take any money.

We kept that going for about a year and a half, two years, but I was starting to feel like there was some stagnation in terms of getting my books into more places as a publisher. I’d been sharing office space in Seattle with Chatwin Books, which is [cofounded and published] by Phillip Bevis, who is also the owner of Arundel Books, an amazing bookstore that I’ve loved for a long time that’s a couple blocks away in Pioneer Square. Phil and I would sit in here after a day’s work, and we would talk about pie in the sky: What if we, a small press, could set the terms? What would those be? The other question was, Can we get away with it?

We firmly believe there’s no set of industry-standard terms that works for Penguin and us. There’s even a gulf—I think people don’t realize—between bigger indies and us, in terms of how we operate. The economics of what it looks like to be even a bigger indie and a true small or micropress is quite different.

Phil and I sat down, hammered out something that we thought might work. We talked to other presses and other booksellers to sort out the model a bit. We looked around at a newly empty space and said, “Well, we’ve got warehouse space. Why don’t we give this a go?” Phil and I relaunched Asterism in February 2023. We’re the co-owners of Asterism. We do not have any outside funding sources.

Like so much related to making books and selling them to readers, this venture potentially implicates technology.

I, most recently, was an engineer for the Seattle Times. I’ve always worked in and around the media space. I’ve worked for magazines, media websites, and then, most recently, newspapers. This intersection of tech but also valuing the words that human beings write that are sometimes printed has been central in my career.

I wrote all the software myself. That was part of why we didn’t really have a lot in terms of, like, startup costs. Software is expensive, especially enterprise-level software that deals with inventory or accounting or things like that. For a lot of these things, we’re able to rely smartly on some vendors that aren’t breaking the bank, but most of the core proceedings of the website work according to code I’ve written. My career has often involved not necessarily user-facing products—though I enjoy that part, too—but tools. I’ve worked on developing content management systems and workflow management systems at various jobs, and that came in nicely here with, What information does a press need?

For instance, you log directly into the site as a press, and, lo and behold, you have a sales report that shows where all your books are going in real time. There are definitely challenges and new things to learn, but we’ve been able to be really flexible and pivot quickly when we needed to and also be able to take feedback from presses or come up with new ideas. Someone says, Hey, we should try this, and [we say] OK, that will take a couple hours. Let’s try it. We’re able to be nimble.

Are you placing restrictions on which publishers will join you in this collective?

We have been expanding. We announced that we had warehousing and fulfillment space about two days before SPD announced the closure of the Berkeley warehouse. AWP [Conference] was a week or two later. We had 13 presses on the active roster at AWP in Seattle in 2023. We have 56 presses now, including a couple that were in the process of coming over from SPD when this happened.

We realize we’re a lifeboat for a lot of people right now, but the last thing you ever want to do to a lifeboat is overload it, so we’re making careful calculations in terms of what stock we think we can take on. SPD had something like 300,000 books still in the warehouse. We’re estimating we could take on an additional 100,000. SPD had something like 360 to 370 presses. We’re going to try to take on as many presses as we can. It won’t be all of them. I think it’ll be probably in the order of 80 to 120 new presses.

What is the process?

We’re trying to expedite. Normally, if a press applies, we say, Let’s set up a one-on-one meeting with you. We’ll talk about what we do, what we don’t do, because we don’t do everything a traditional distributor does. At that point, if a press is still interested, we’ll talk internally; we have an advisory board of presses.

We’re looking for people that we think we can get behind, whose books we can sell, because our model is entirely based on us selling these books. We don’t charge warehousing fees; we want our incentive to be on selling books that fit with our catalog. We’re not actively taking on genre publishers, and it’s not because I have any animosity or snobbery about the phrase literary. It’s just that we can only sell what we know how to sell.

What do you think are the benefits to readers, potentially, of a different distribution model?

We’ve built a much more consumer-friendly, reader-facing website. If you go to our home page, you’ll see we display, almost, “shelf talkers” to make it feel more like browsing in a physical space. We’re about to be one of the biggest marketplaces online for small-press books, and that’s always a good thing. One of the reasons we can offer friendly terms is we don’t have a real interest in being a middleman to other middlemen, so we work closely with bookstores. We have more than 200 bookstores we’re working with now, and we’re adding new ones daily at this point. Readers may find more of these books in bookstores, and I hope that’s what we can get for them.

Are there benefits for physical bookstores?

We are bullish on bookstores. I think physical bookstores are going to need to differentiate from the online space, where you’re seeing all the same books. That’s why we don’t sell into Amazon and into other places that are pass-throughs that end up, like, heavily discounting the books more than a bookseller can sell them for. That’s one of our core tenets: while our publishers can have a real direct relationship with Amazon or even use Lightning Source or Spark to get books on Amazon, and we’ll almost certainly introduce, like, a marketplace integration where we can ensure the books stay at list price, our commitment as a company is that we don’t sell the books to Amazon so that they can mark them down and take those sales away from booksellers.

We think these are items that will sell for bookstores. Phil’s a bookseller, and he’s the first person to say that the books sell; that’s why he was confident in the ideas. He’s seen how they’ve done in his bookstore, competing against other titles. I believe Phil has told me that something like 8 of his top 100 sellers in the last year and a half are Asterism titles—and that’s competing with Rupi Kaur on the front counter.•

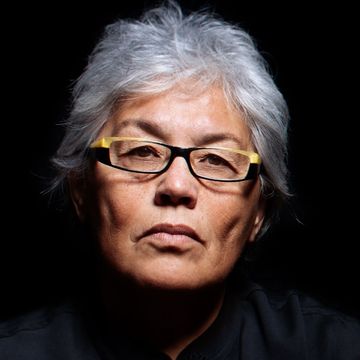

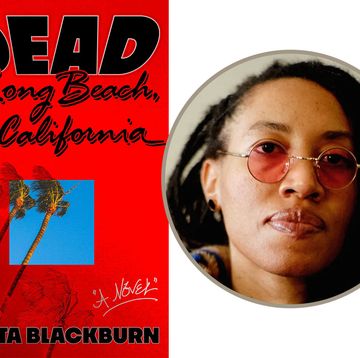

Join us on April 18 at 5 p.m. Pacific time, when author Jessica Hagedorn will appear in conversation with CBC host John Freeman and special guest Sean San José to discuss The Gangster of Love. Register for the Zoom conversation here.

Anita Felicelli, Alta Journal’s California Book Club editor, is the author of the novel Chimerica and Love Songs for a Lost Continent, a short story collection.