The mind-brain problem has spurred numerous philosophical inquiries in the contemporary age. Can we, for instance, hold people entirely responsible for their actions when so much of biology, including diseases of the brain, determines behavior? What are the implications of that for the criminal justice system? One of the most intriguing philosophical problems with implications for technology is qualia. This concept has somewhat multivalent philosophical definitions, but broadly, it refers to the ineffable and private experience of what it subjectively feels like to engage in a sensory experience.

When philosopher Thomas Nagel asked, “What is it like to be a bat?” in his famous essay of the same name, he urged that we can’t know what it’s like to be a bat, with its very different sensory perceptions. We can only know what it’s like to be us imagining our experience as bats. Thinkers who regard the mind as purely grounded in the material and rational, like Daniel Dennett, take a different approach—for Dennett, there is no such thing as qualia. He has written, “Qualia seem to many people to be the last ditch defense of the inwardness and elusiveness of our minds, a bulwark against creeping mechanism. They are sure there must be some sound path from the homely cases to the redoubtable category of the philosophers, since otherwise their last bastion of specialness will be stormed by science.”

When we, the reading public, consider robots and artificial intelligence, we may not use the term qualia, but we regard them as different from us precisely because they have no qualia, even if they are able to behave as if they do, recoiling at something we find gross or stating a baby is cute. What alarms many of us about robots is that they are increasingly able to behave like humans—writing novels, making art, driving cars, washing the dishes—without qualia, and so we wonder if they may eventually develop consciousness, interiority, and therefore free will.

I’d go a step further and say that the tension that exists between novelists and proponents of artificial intelligence occurs largely because most novelists believe in the primacy of qualia. Their work depends on believing that every human has their own take on what various things feel like—interiority—and has, at least in part, agency and free will to influence the events of the novel.

Dave Eggers takes up the question of qualia and the mind-brain problem memorably and with distinctive creativity in his disturbing comic novel The Every, the February California Book Club selection. The book tells the story of a tech skeptic, Delaney Wells, who decides to infiltrate and bring down the Every, a corporation modeled on Google that has bought an e-commerce site modeled after Amazon. Both Google and Amazon, in real life, rely heavily on data mining, and like other Big Tech companies these days, they invade and co-opt people’s attention while also collecting information that people a few decades ago would have regarded as private.

Eggers pushes that reality much further. While several blocks away from Google headquarters, many people (like me and my neighbors) tend to love being in nature to a notable degree, don’t spend much time on social media, and tend to encourage our children, at least, to pursue art, in The Every, the eponymous company is peopled by number-oriented capitalists whose concerns blend 1920s East Coast efficiency-movement ideals and Philadelphian Taylorism with an animosity toward subjective experience. This clinical animosity in the book takes the form of efficiently monitoring and figuring out at what point people lose interest in fiction—when a character is unlikable. Never mind, in this analysis, that a novel may be thought-provoking and allow a reader to see something he or she might not otherwise imagine.

Almost midway through the novel, Delaney takes a busload of coworkers (“Everyones”), selected by algorithm, on an excursion to the portion of the Point Reyes shore formerly known as Drake’s Beach to watch elephant seals mating. The journey there is fraught, as the Everyones get sick over “animal bondage.” Perhaps the most telling moment, however, is when the group expresses its collective horror at nature in the form of the “ugly and vulnerable and loud” elephant seals at Point Reyes. Delaney assumes that the Everyones will see the miracles of nature that she sees, but instead, “many people spoke of the beach itself as a source of discomfort, containing as it did too much water, too much sand, too little guidance, and the presence of seal infanticide.” They retreat to the bus.

In our reality, elephant seals are lolling beasts who are horrifying when they slam their giant bodies against one another in battle. Their movements are nonetheless attention-grabbing; if you stand out there on the coast looking at them lounging together or mating or fighting, it’s difficult to turn away. And the experience of them in the chilly wild is adjacent to the experience of the sublime—the fear they can engender is also a quality of grandeur, a sense that there are beings in the world whose overwhelming and magnetic qualities, unlike those of charismatic megafauna, lie a little bit outside our ability to explain or catalog or make sense of them. What does it feel like to be an elephant seal? Their existence is the opposite of how the Every wants to remake the world: strictly understandable and nice but also, for those reasons, sterile and mechanistic.

As Eggers humorously frames some characters’ viewpoint, “it was agreed that forty-two people arriving aboard a giant steel machine to watch seal families mate and abandon their young was wildly aggressive and inherently exploitative. Someone called it Darwin-porn.”

The cleverly executed brilliance of Eggers’s novel is that it actively reconceives fiction itself by using tactics similar to the Every’s. Within these pages, behavior comes to be all, the only thing worth paying attention to because it can be quantified. Interiority exists but is limited—human messiness is gradually quelled through niceness and proclaimed utopian values. Qualia barely exist; there are no long passages of sense memory in these pages, for example, and you can imagine Dennett thinking in the background, Yes, this is how humans are. Eggers frightens us by showing us a world of seemingly good intentions collapsed under mechanical systems that aggressively strip away the humanness of humans.

Eggers’s artistic departure from traditional craft elements, for purposes of showing us something about what our lives might be like if we allow our inner experiences to be taken over by Big Tech, is notable. As a novelist, designer, publisher, and human rights activist, Eggers surely believes in qualia, but rather than take the more mundane step of working within the usual literary realist tactics of conveying the interiority of humans as essentially untouchable and unchangeable—still attentive, for example, to sense memory in a world entirely defined and dominated by metrics—he suggests that in a dangerous future in which human consciousness has been utterly reorganized by invasive and mechanistic technologies, qualia would cease to play a role, would cease to distinguish us from robots.

From his debut, A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, onward, Eggers has been concerned with the tangible, the beautiful, the messy, dignity, the human being. He is unafraid to consider what it’s like to be a bat—to write his recent Newbery Medal–winning children’s book, The Eyes and the Impossible, he had to imagine the world as a dog. His projects with his independent press, McSweeney’s, are similarly focused on the luscious and the authentic. With The Every, he employs techniques that he uses in other novels and his human rights advocacy to argue for the inherent dignity of human beings—however unpredictable, messy, wild, and, yes, beastly, we are.•

Join us on February 15 at 5 p.m. Pacific, when Eggers will appear in conversation with California Book Club host John Freeman and special guest Caterina Fake to discuss The Every. Register for the Zoom conversation here.

ART AS AI

Bridget Quinn writes about the making of art in the age of AI. —Alta

KEEPIN’ ON, THE RICHARDSON DYNASTY

Ishmael Reed explores the historical role of Black community support in allowing the oldest Black bookstore in the country, Marcus Books in Oakland, to stay in business. —Alta

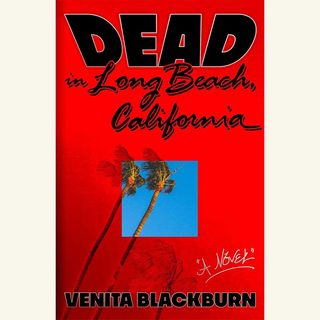

SCIENCE FICTION DOUBLE FEATURE

CBC editor Anita Felicelli reviews Venita Blackburn’s Dead in Long Beach, California, praising it as a “conceptually ambitious, delightfully queer novel.” —Alta

FEBRUARY RELEASES

Here are 11 books by authors of the West we’re excited about. Among them is Wandering Stars, the second book of past CBC author Tommy Orange. —Alta

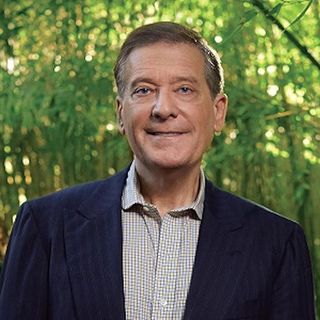

PSYCHOLOGICAL WHODUNIT

Read a profile of Los Angeles crime novelist Jonathan Kellerman, whose latest Alex Delaware mystery, The Ghost Orchid, publishes today. —Alta

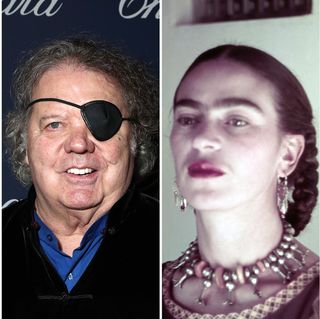

“JACKIE ROBINSON OF BIRACIAL COMEDIES”

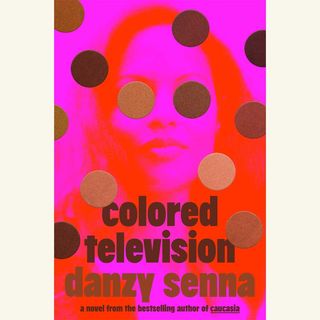

CBC selection panelist Danzy Senna reveals the cover of her next novel, Colored Television, and has a conversation about how Hollywood shifted her perspective on books. —Elle

Alta’s California Book Club email newsletter is published weekly. Sign up for free and you also will receive four custom-designed bookplates.

Anita Felicelli, Alta Journal’s California Book Club editor, is the author of the novel Chimerica and Love Songs for a Lost Continent, a short story collection.