In The Other Americans, Laila Lalami unfolds a carefully balanced drama, and part of that is starting with the question of who committed a hit-and-run. Based on the circumstances, the crime wouldn’t naturally inspire curiosity about whether it was a hate crime and whether it should be investigated as such. While characters do tangle with the system in the hit-and-run investigation, the larger problem here is unspoken xenophobia and working-class resentment. Lalami refuses an easy answer, which is the power of a novel, but the pervasive, larger social problems are still fully illuminated by our access to the characters’ interiority and, up until a late scene, by subtle aspects of how they behave.

As people who are facing a moment when all these social problems are coming to a head, and leaving many of us unsteady, we also might be considering the existential quandary of how to respond when the system won’t or cannot address social problems and those problems feel too big and diffuse to fix. As a citizen and not an elected representative, you can’t truly repair what’s happening on an individual basis—your greater hope is to find a group of people who believe, as you do, in justice—nor can you walk around, one by one, and handle through interpersonal relations the issues that are the air we breathe as 21st-century humans.

Because here’s the thing: unless we capitulate to the notion of algorithms administering justice, we have the grace that most of the workings of the “system” are executed by people, and there are, in the machinery, spaces where individual people’s discretion directs the course of events, even when the language of the law is as transparent as possible.

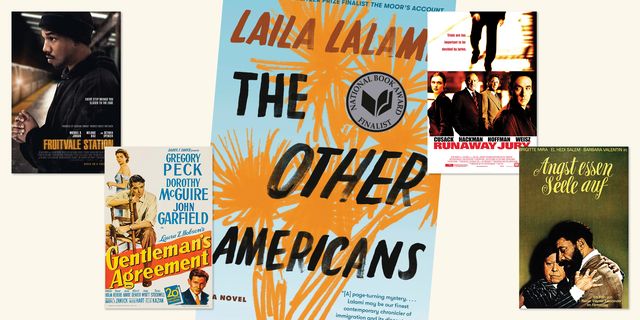

The advantage of novels is that they allow you inside a character, but filmmaking requires a different tack; the acting and the action take on most of the heavy lifting of making us care about the story. One of the movies that come to mind in connection with The Other Americans’ handling of the intersection between the structural and the personal in the context of police brutality and racism is Ryan Coogler’s Fruitvale Station. Very early on New Year’s Day 2009 at Oakland’s Fruitvale BART station, a young Black man, Oscar Grant, was fatally shot by a BART police officer. Fruitvale Station is the biographical drama woven around what led up to the manslaughter and opens on the death itself. The fact of the death, like the fact of the hit-and-run in Lalami’s novel, triggers the audience’s questions and the concomitant suspense—what happened to get us here?

The movie portrays Oscar, played by Michael B. Jordan, in the lead-up to his getting killed. Shooting the film almost entirely with a handheld, Coogler places us within an ordinary day, with its disappointments and pleasures. The incredible verisimilitude of life in Oakland makes this among the best films I’ve seen set within the area. In one scene that clues us in to a more tender side of him, Oscar calls his grandma so that she can tell a customer at the store where he works how to do a southern fish fry for her boyfriend. When we arrive at a giddying scene where someone busts out speakers on the BART train and everyone in the car dances to the music and shouts “Happy New Year!” before the clock turns and fireworks go off, we’re devastated, waiting, hoping that what we know will happen won’t.

Hollywood classic Gentleman’s Agreement, directed by Elia Kazan, who won Best Director for his work, is about a California journalist, Philip Schuyler Green, a gentile who travels with his aging mother and son to New York City for magazine work and gets pitched the idea of reporting on anti-Semitism for a magazine. Skeptical of the severity of anti-Semitism, Philip pretends to be Jewish in all aspects of his life, posing his son as Jewish, too, and is horrified—just two years after the Holocaust—to discover that he was wrong and that anti-Semitism is alive and well in New York. The premise here is sort of traditional Americana. Like other such movies predating New Journalism, or even dating from before the past five years or so, it presumes that the audience will be most interested in a setup where a good-looking, clean-cut white man can lend his credibility and privilege to lambaste social wrongs that profoundly affect others but not him, as opposed to centering on the person who experiences those injustices organically.

Philip, played by Gregory Peck, says of an anti-Semitic incident, trying to figure out with what angle he should approach the magazine series, “What must a Jew feel about this thing? Can I think my way into [my Jewish friend] Dave’s mind?” He thinks that there are some questions you can’t ask another person and that the only way he can understand what his friend feels is if he feels it himself. Referring to another piece of journalism he reported about coal miners after living as if he were one, he tells his mother, “I found the answers in my own guts, not somebody else’s. I didn’t ask somebody what it feels like to be an Okie. I was an Okie.” The drama of how cruel bigotry can be is left underexplored, for these perpetrators are “gentlemen,” and as one character honestly observes of the upper middle class, “you can’t pin ’em down, Phil. They never say it straight out or put it in writing. They’ll worm out of it one way or another. They usually do.” Still, there’s a spark of something here, a sense of wholesome righteousness, a certainty that justice might be available through journalists. Is it possible, we might ask at this moment in history, to truly move people toward justice on the basis of this kind of appropriated “objective” narrative—is the potential for a shared feeling of justice among different groups passé?

Some of the most satisfying movies, though, are those that look into the effect of interpersonal dynamics on the legal system—these days, Hollywood incorporates bleak news by allowing the satisfaction of a win by underhanded means. There’s a reason so many defense attorneys with a conscience say they’ve left the dark side when they switch to plaintiff’s work. The binary dynamic of American civil-trial work to address social ills is illustrated powerfully and entertainingly in Runaway Jury, starring John Cusack, Rachel Weisz, Dustin Hoffman, and Gene Hackman. After a heartbreaking opening scene in which a woman loses her husband in a mass shooting, we watch the devastated woman seek recompense from a large gun manufacturer. Hoffman gives a pitch-perfect performance as the folksy sort of plaintiff’s attorney who can secure giant verdicts—justice-focused, persuasive, able to tell a story that speaks to the heart rather than focusing on technicalities, and led by strong insights into personalities and people. Jury selection is one important aspect of winning trials, but the insights that lead to millions often happen long before for successful plaintiff’s attorneys, starting with client selection. Hoffman’s character is up against a nefarious jury consultant (Hackman) hired by the gun manufacturer to use any method necessary, including illegal and evil ones, to secure a verdict for the defense.

What neither anticipates is that one of the jurors is working with a woman on the outside to sway the jury. The jury box is one of those interstices within the system’s machinery where interpersonal dynamics play an outsize role in justice. When a trial lawyer with resources presents good evidence and arguments and avoids making technical errors for defense attorneys to seize on, they offer ordinary people the chance to feel empowered to do the right thing, even before they get to deliberations—however, in the jury room, there are many moments in which interpersonal dealings between jurors play a prominent role in the outcome, shocking even the most experienced attorney.

Runaway Jury presents a pivotal scene in the multicultural jury room that, like The Other Americans, illustrates the extent to which grievances from people’s personal pasts affect how much empathy they are able to feel for a victim and how they view the law as well. Too often, a juror has been fooled by tort reformists and inaccurate information about how the law works (think the McDonald’s lawsuit involving third-degree burns over a plaintiff’s genitals) into believing that victims are moneygrubbing and looking for handouts. Resentment so often propels people’s choices in how to treat others, and that alone serves as an ever-present stumbling block to social change—one that wrongdoers are happy to exploit.

And xenophobia and other discrimination happen all over the world in other judicial systems and under other social expectations. A foreign film that occurred to me in connection with The Other Americans was Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s movie Ali: Fear Eats the Soul, which examines Islamophobia against a Moroccan immigrant, only this time in Germany. It also considers ageism. Fassbinder’s movie is a reworking of All That Heaven Allows, which examines class in America. Beautifully and harmoniously shot in vivid tones, it’s a mirror in some ways to the harmonious aesthetic of The Other Americans. The premise is simple: A Moroccan immigrant, Ali, meets a much older German widow at a bar, and they fall in love. Both find themselves dismayed by the amount of prejudice their friends and cohorts exhibit toward their partner. Ali faces anti-Arab bigotry from people the older woman knows, and she faces cruel gossip and what that spawns in turn.

During a card game the two play with Ali’s friends, the woman’s neighbors complain about a noise disturbance and get the system involved by telling police when they arrive that she has four Arabs living with her: “You know what they’re like. Bombs and all that.” Like one of the characters, Jeremy, in The Other Americans, the woman realizes that her friends are prejudiced against Arabs and feels the urge to protect her significant other. Their relationship is threatened by the incursion of other people’s disrespect toward their identities.

Imagine if all the people of California and this country showed true solidarity, fighting as much and as hard for justice for one another in these interstitial areas of the legal structure as they might for themselves. What chance would an oligarchic system have against us then? During his last concert at Yoshi’s in Jack London Square on January 9, 2020, beloved, peace-loving alternative-rap artist Gift of Gab of Blackalicious, who would die the following year, shouted into the joyous crowd, “It’s about the good people of the earth against the bloodsuckers.” I still think about that.•

Join us on March 21 at 5 p.m. Pacific time, when Lalami will appear in conversation with Alta Journal books editor and California Book Club guest host David L. Ulin and special guest Danzy Senna to discuss The Other Americans. Register for the Zoom conversation here.

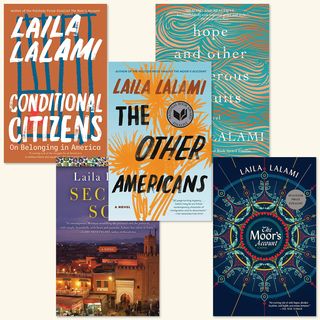

LALAMI’S FIVE BOOKS

Critic and author Ilana Masad writes about themes of alienation and home as they arise in Lalami’s body of work. —Alta

GRAND ENTERTAINMENT

Critic and Alta Journal contributor Michael Schaub reviews translator Jennifer Croft’s debut novel, The Extinction of Irena Rey, calling it a “wild ride” and “simultaneously unsettling and hilarious.” —Alta

MAKING OF A TRAVELOGUE

Alta contributor Joy Lanzendorfer writes about John Steinbeck’s six-week voyage to Baja, Mexico, with his wife and the biologist Ed Ricketts, which led to The Log from the Sea of Cortez. —Alta

DESERT CHIC

Author and Alta contributor Jennifer Lewis profiles Amanda Zo, the Joshua Tree designer, entrepreneur, and motorcyclist behind the “heavy metal” clothing made by Chain Driven Apparel. —Alta

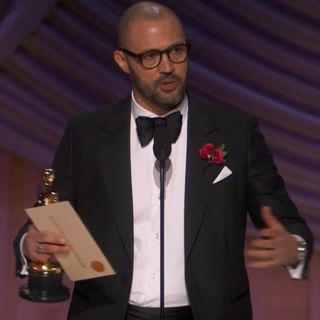

RISK-AVERSE INDUSTRY

In the Oscars acceptance speech for his adapted screenplay of prior CBC author Percival Everett’s Erasure, Cord Jefferson movingly called on Hollywood to give more up-and-coming creatives a chance to make films. —Deadline

“TWO VIOLENT STORMS”

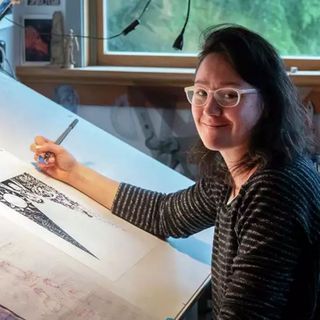

Brandon Yu writes that Bay Area–raised artist and writer Tessa Hulls’s graphic memoir, Feeding Ghosts, takes on “with devastating emotional acuity, the line between the history of China under Mao Zedong...and the ghosts of her family’s past that she eventually unearthed.” —San Francisco Chronicle

Alta’s California Book Club email newsletter is published weekly. Sign up for free and you also will receive four custom-designed bookplates.

Anita Felicelli, Alta Journal’s California Book Club editor, is the author of the novel Chimerica and Love Songs for a Lost Continent, a short story collection.