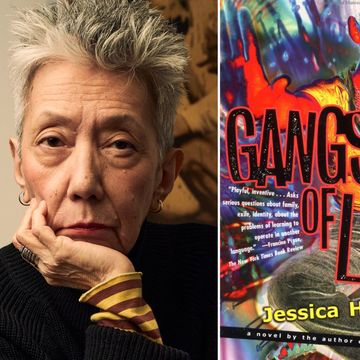

Rock music, like baseball, is a tough subject for fiction. That’s because the reality is strange enough. Four teenagers from Liverpool become the Beatles? A Seattle junior high schooler, last name of Hendrix, discovers a one-string ukulele and reinvents himself? I mention Hendrix because his death in 1970 at age 27 becomes a driver, of sorts, for Jessica Hagedorn’s The Gangster of Love, which remains for me one of the few rock ’n’ roll novels that really work. “Jimi Hendrix died the year the ship that brought us from Manila docked in San Francisco,” Hagedorn’s narrator, a teenage Filipina named Rocky Rivera, informs us at the start of this looping, episodic narrative. “My brother, Voltaire, and I wept when we read about it in the papers, but it was Voltaire who was truly devastated. Hendrix had been his idol.”

Much of what makes Hagedorn’s novel so effective appears in those sentences: the circumstance, the adoration, the voice. We err when we think of rock as exclusively about the artists. Like all commercial forms, it has as much if not more to do with the fans. That’s not to say there isn’t art in it; just listen to any Lennon-McCartney recording or to Hendrix’s virtuoso finger work if you have doubts. Yet even Hendrix, who was less a pop star than the antithesis of one, couldn’t help but become an icon, a guitar hero, more than a bit larger than life.

This article appears in Issue 27 of Alta Journal.

SUBSCRIBE

That’s the draw for those who love it: rock ’n’ roll as a narrative of liberation, which we, in turn, vicariously fulfill. The Gangster of Love represents a case in point. The story belongs more to Rocky than to her brother, although he exists in it, as does her boyfriend, a guitarist named Elvis Chang, with whom she starts a band. The arc of that band, called the Gangster of Love, reflects the novel’s own. Hagedorn is not a strictly naturalistic writer; as in her 1990 novel, Dogeaters, she interweaves history and myth. The effect is a universe in which logic is not enough to explain experience, the way our lives surprise us in the end.

For Rocky, this is as much a matter of family as music. She and Elvis take the band to New York, where they break up. Meanwhile, back in San Francisco, her mother’s health is deteriorating, and Rocky is called to care for her. Eventually, Rocky decides to go back to the Philippines rather than return to the East Coast.

The idea is that home is everywhere and nowhere, which is also an essential tension in rock. How many songs are there about the lure of it, getting back to where you once belonged? “What’s Filipino?” Hagedorn wonders. “What’s genuine? What’s in the blood?” A related set of questions might be asked of rock ’n’ roll, which is nothing if not a derivative form. The trick is that in rock as in The Gangster of Love, something authentic emerges from the mash-up of styles and influences, something vivid and complex.•