As a previously undocumented person in the United States, I’ve always known I am a second-class citizen. Even now, with an “Extraordinary Ability” visa, I could be deemed deportable. I’ve never had the privilege of voting: I do not know what that power feels like, and yet politicians keep making decisions for me and millions of people like me who may be residents but are not citizens. We have no say in decisions that affect us or in administrations that want to deport us, to build a wall that does not work, to jail us within for-profit detention centers. It has taken me years to explore what it feels like to live as a second-class citizen. I still don’t know the answer, but fear is at the root of it. As a teenager, I used anger to cover my very real fear of discrimination and deportation. Assimilation became another blanket to hide this fear. Between the ages of 9 and 17, I learned to hide that I spoke Spanish and wasn’t born in this country. I wanted to fit into “American society” in order to evade the question “Do you have papers?”

This article appears in Issue 27 of Alta Journal.

SUBSCRIBE

During this time, my English teachers seemed to have read only books written by people who didn’t look like me. Then, in 2007, as a junior in high school, I discovered Pablo Neruda’s Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair. The same year, I read Che Guevara’s The Motorcycle Diaries. These two books were small leaves that fell on my hands from a huge tree outside the white literary canon. I learned of June Jordan, Claribel Alegría, Yusef Komunyakaa. When I googled “Salvadoran writers,” the first name that came up was Roque Dalton. I asked my parents whether they knew of him. “Yes, he wrote like us, he is of the people,” they replied. This made me curious enough to buy his Clandestine Poems, which gave me the language to begin to ask my parents questions about their time in El Salvador. They told me about the civil war (1980–92) and the vast inequities that led to the fighting. They recalled La Generación Comprometida—a group of Salvadoran writers born in the 1950s who believed that writers should be at the vanguard, dreaming up a world of gender equality, of democracy, of freedom of speech and thought.

A world that still doesn’t exist.

For the first time in my life, I was convinced of the power of literature. Being from El Salvador meant I could belong to this rich lineage of writers who were read by the rural poor, like my parents, not only by the elites. Through writing, I have been given the gifts of confidence, community, agency. It became the tool that showed me I could also insert myself into whiteness, the whiteness of the blank page. When I googled “immigrant writers,” I saw names such as Reyna Grande, León Salvatierra, and Javier O. Huerta. But none were from El Salvador—my little country. Privately, I vowed to do what these writers had done: reclaim my identity unapologetically.

Through writing, I saw how I had learned to be ashamed of myself. I had begun to absorb the anti-immigrant sentiments I encountered in the news, movies, and literature. Each negative connotation, each micro- and macro-aggression, felt like a burning sticker on my body. I was weighed down by them. And so, I began to write about the childhood that had been taken from me. I began to be proud of my trauma, of surviving the desert in order to get to this country. This reclaiming is still my aim. At 34, I want to show other immigrants, citizens, and noncitizens that being nonwhite doesn’t make us subhuman, that being an immigrant is not a crime. I continue to dream of a world that centers immigrants, through the lens not only of our suffering but also of our humanity. I write for other Chepitos around the world, and for the politicians and others who still refuse to accept that we are fully human beings.•

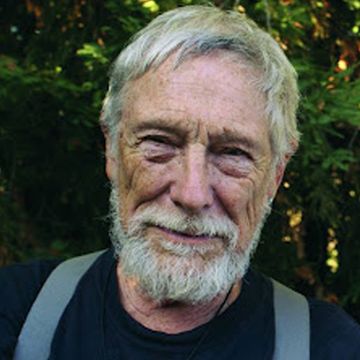

Javier Zamora was born in El Salvador in 1990. He is the author of the poetry collection Unaccompanied and the memoir Solito, which won a Los Angeles Times Book Prize.