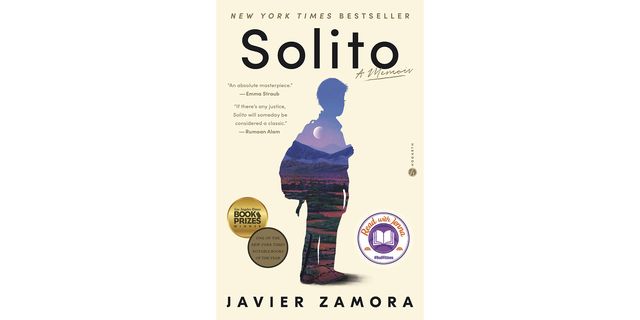

Javier Zamora begins his memoir, Solito, with an epigraph by theologian Katie Cannon: “Our bodies are the texts that carry the memories and therefore remembering is no less than reincarnation.” It’s a telling statement, one that might apply to the whole art of personal narrative, but it feels especially appropriate to Zamora’s work. A poet—his collection, Unaccompanied, came out in 2017—he writes with uncommon sensitivity: to circumstance, to language, to the way emotions and states of being roil like a web of overlapping lives.

Certainly, this is the case for Zamora; a graduate of UC Berkeley and more recently a Wallace Stegner Fellow at Stanford, he was born in El Salvador in 1990 and, when he was nine, journeyed to the United States to join his parents, who had come north before him. That seven-week journey provides the spine of his book, although to call Solito a coming-of-age story is to miss the point. Rather, it keeps the focus on the moment, the experience of migration, the daily grind of it. Zamora—or Chepito, as he is called—is not alone, but he is without family or loved ones, navigating the 3,000-mile crossing with a coyote named Don Dago and a collective of fellow travelers. The care the latter show for one another, their mutual empathy, offers a potent lesson in humanity.

This article appears in Issue 27 of Alta Journal.

SUBSCRIBE

Zamora’s decision to frame Solito from the perspective of a nine-year-old is risky, but it pays off. Because so many narratives of the southern border come steeped in policy, it’s refreshing to encounter one that unfolds entirely through an individual lens. Not only that, but the child’s-eye view also allows Zamora to take a more intimate approach to an overwhelming situation. Chepito must learn to fend for himself: to wash his clothes, to keep his counsel, to read the signs. He learns whom he can trust and whom he cannot. He also expresses a visceral longing, unmitigated by the knowingness of an adult. The innocence of the narrator works as a contrast to the dangers he is living through.

“I don’t want to go back to El Salvador,” Zamora writes. “We take a few steps forward. Chino smells bad. I smell bad. The people in front también. Sweat. Dust. Sardines. Piss. I can’t wait to shower. I look at Patricia’s lips, and there’s a flower bursting through them. A fire. The beginning of a cold sore. Mamá Pati gets those. I get them. ¿Did she have a fever in the cage? ¿The temperature change? I don’t want a fever.”

Follow the progress of that paragraph and what you get is something like a stream of consciousness, the movement of the mind as it catalogs what it’s engaging, an ongoing present tense. Break it out and it could read like a poem, which is the whole idea, as is the integration of the inverted question mark and the Spanish “también.” Zamora uses such effects throughout his book to delineate a second story, in which who we are and where we’ve been all blurs together in memory and imagination, creating a language, a narrative, that belongs to each of us alone.•