In roughly the time it’ll take you to read this essay, someone in the state of California will be injured in a hit-and-run accident. Nearly nine people an hour, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, are injured, according to the most recent data (2018–2020) from California Highway Patrol. It’s an extraordinary fact. Add to this about one hit-and-run fatality per day and it looks like the Golden State has an epidemic in coexistence. Of all crimes, hit-and-runs tear at the weaker seams of a society, those who may or may not know one another. We are, indeed, vulnerable simply by living together—walking the same streets. Driving the same roads. Driving two-ton SUVs or, god forbid, riding a bicycle. If we agree on rules applying equally and offering equal exposure, then perhaps a society works.

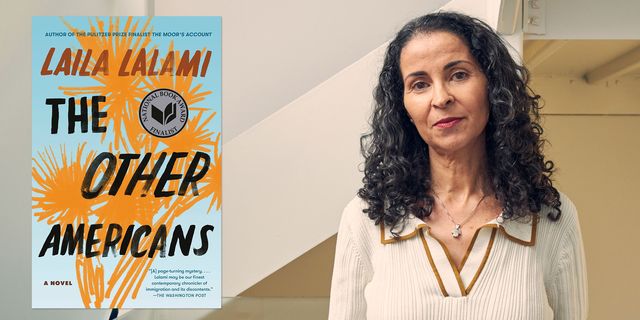

But it doesn’t really work that way, does it, because the stress doesn’t fall equally. Take this from the cast at the heart of Laila Lalami’s The Other Americans, her 2019 novel, which begins with the hit-and-run death of Driss Guerraoui, a hardworking immigrant who had just begun to live a life in which he made choices rather than adapt to forces outside himself. “My father had often outrun disaster,” his daughter Nora, one of the book’s nine narrators, says. “The protests in Casablanca had moved him to California; the arson had made it possible for him to buy a diner. But now disaster had finally caught up with him.” The arson mentioned here is one of the rips in the fabric of the community where The Other Americans takes place; the novel is set in the Mojave, 10 miles from Joshua Tree National Park, in a town along Highway 62 where change has come and some are more comfortable with those social shifts than most. Driss and his family were part of that change, transplanted to California after the crackdown on protests turned violent in Morocco. And yet he thrived. Working diligently, buying a failing doughnut shop and renaming it Aladdin Donuts. Not long after his wife, Maryam, had been able to leave the business to help raise their kids, it was burned down. A retributive arson post-9/11.

For this reason, when Driss is killed, Nora’s first thought is that what has happened to her father was not an accident. The Other Americans takes place mostly in the aftermath of this event, this uneasy question hanging in the air as the novel orbits through its large cast, all of them touched, in one way or another, by Driss’s death, many of them with experience enough to have similar doubts. Efraín, a Mexican man who saw the moment Driss was hit, is afraid to come forward; when he reads the name of the victim, he realizes how close it is to Guerrero. How easily it could have been someone like him.

Lalami has written brilliantly about the perils migrants face in her fiction before—often in a direction heavily tilted toward the past. In Hope and Other Dangerous Pursuits, a boat carrying a group of Moroccans crossing the Strait of Gibraltar to Spain capsizes, and in flashbacks, we learn what conditions brought them to a dodgy raft on high seas. Her dazzling The Moor’s Account narrates the journey of Estebanico, the first person of African descent to explore the New World—a journey full of peril and danger, from Florida to Mexico. Several times during the journey, Estebanico buys himself into freedom.

In her essay collection, Conditional Citizens: On Belonging in America, Lalami writes about her own journey from Morocco to the United States and about becoming a citizen in a country where people like her—a woman, an Arab, a Muslim—often have to prove their innocence, even in the absence of a crime. This trajectory suggests that The Other Americans would become a kind of argument in the form of a fiction—but it is a far subtler book than that.

Whereas Lalami’s previous fictions reveal the perils of surviving, The Other Americans deals with the problems of belonging. In the novel, Nora has a tattoo on her wrist of words in Latin that mean “a voice crying out,” presumably a reference to “vox clamantis in deserto,” which might be a shortened form of a quote from St. John the Baptist. Among the things that the passage addresses is the need to repent. But also—the power of a voice. Coexistence requires both—voice and listening.

The Other Americans is one of the only novels of its type that understand the necessity of both. Moving along its narrative wheel, Lalami’s book reveals unexpected and moving parallels. Coming home to bury her father, Nora encounters Jeremy Gorecki, a onetime honors student like her whose life hasn’t gone as planned. His mother died young, and into that rupture, he poured himself, covering for a father who drank. While Nora fled to become a composer, he fled into the army—and wound up in Iraq.

Of all the books featuring veterans that have been published in the United States in recent years, The Other Americans is among the very best. While Jeremy’s story is one of knocking down doors in the dead of night in Iraq, terrorizing families, he has other memories, other elements to his personality—and the book isn’t distorted to acknowledge only his trauma. In fact, his experience of nearly being killed far from home has made him appreciate—all the more—what Nora’s family has gone through, even before the accident. This sensitivity is so rarely portrayed in veterans in fiction, who are often, for purposes of drama, written as damaged beyond repair.

In one of the most striking scenes of the book, Nora flees the excessive ministrations of her mother, and a new secret that has emerged from her father’s life, to a bar. Jeremy sees her crossing the street and decides to follow her in. She has a drink—he, a few years sober, a burger. They begin to connect, and then she asks a question that forces him to reveal to her—an Arab and a Muslim—that he fought in Iraq. The slow, subtle way the confrontation happens, and its erotic aftermath, is one of the finest collisions in recent American fiction.

If Hope and Other Dangerous Pursuits and The Moor’s Account deal with characters traveling toward and through a place, everyone in The Other Americans is, in some way or another, stuck in the environs of the Morongo Basin. For a swift if sprawling book set in the desert air, with a few hikes thrown in, the novel feels claustrophobic. People run into one another. People see one another doing things. Time is spent in cars and crummy shopping malls. At last, here is a novel that feels like what it feels like to be in the United States.

Narrating all this in multiple first-person voices—with one brief foray into second person, when we hear from Nora’s sister—requires a fine-tuned musical register. Lalami has it. The characters in the book do not so much narrate as speak into the air. Somebody one day will make a superb play or opera out of this novel; a great deal of the work is already done. One by one, characters emerge and speak, often quite briefly, for two or three pages at a time, each with different accents and habits.

The Other Americans exists in that gray space on the continuum between everyone speaking and everyone occasionally listening to one another. Only one character doesn’t do so much listening—Anderson Baker, who has been in town the longest. He’s the owner of a bowling alley, a father late in life, and his is a world of people like him and “the other Americans.” “Some people say I should be grateful for the business that the newcomers are bringing to the town,” he says at one point. “But the way I see it, they’re changing this place and wanting me to be grateful for it. They didn’t ask if we wanted them here, and they just came.”

Ultimately, the narrative strategy of Lalami’s novel becomes a kind of philosophy. Moving character to character, it seems not just natural but right that people would compare their fates. Measure what one person had and what another person didn’t. At the root of the mystery of Driss’s death is a comparison of this kind made by a person jealous of what Driss was able to obtain—even if that envy didn’t become a weapon, it was a form of violence.

Can an accident be a weapon? The Other Americans is one of the rare books to present one as such, across so many different meanings. It’s by accident—nearly—that Driss missed a bullet in Morocco and winds up in California; it’s by accident that a detective working the case winds up in California and not back East, where she grew up; it’s by accident that one of Jeremy’s buddies saves his life in Iraq, a fact that makes him, throughout the novel, beholden to him, even though the man is a walking fuckup.

Gently, quietly, The Other Americans creates a portrait of life in an uneasy United States of the near present, where accidents are in fact the greater norm, the bigger uniter. The minority are those other Americans, the rare few who have not been brought low by an intervention of fate, by catastrophe. One of the most tragic truths at the heart of this important book is that even among the minority, there are those too proud, too grief-stricken, sometimes too bigoted to acknowledge that they, too, are waiting for a voice to cry out in the desert.•

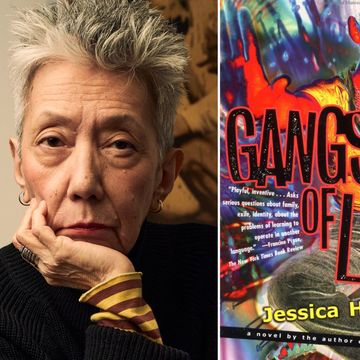

Join us on March 21 at 5 p.m. Pacific time, when Lalami will appear in conversation with Alta Journal books editor and California Book Club guest host David L. Ulin and special guest Danzy Senna to discuss The Other Americans. Register for the Zoom conversation here.

John Freeman is the host of the California Book Club and the editor of Freeman’s, the final theme of which is Conclusions, out this fall. He is the editor of The Penguin Book of the Modern American Short Story and Freeman’s and an executive editor at Knopf. His latest book is Wind, Trees. He lives in New York.